A. Methods

[Some common integration methods:]

- Substitution

- By Parts

- Differentiation of a Parameter

- Series Expansion

- Contour Integration

- Numerical Methods

- Special Tricks

Methods 3 to 7 are applicable particularly to definite integrals.

B. Complex Variable in Substitution

Example: Find: \[ \int_0^\infty e^{-ax}\cos bx \,dx \] [Let’s remember that] \[ \cos bx = (e^{ibx}+e^{-ibx})/2 \] Therefore, the given integral is equal to \[ \begin{aligned} &= \dfrac{1}{2} \int_0^\infty e^{-(a-ib)x} dx + \dfrac{1}{2} \int \dots \\ &= \dfrac{1}{2}\dfrac{1}{a-ib} + \dfrac{1}{2}\dfrac{1}{a+ib} \\ &= \dfrac{a}{a^2+b^2} \end{aligned} \]

C. Differentiation of a Parameter

Example: \[ \int_0^\infty xe^{-ax}\cos bx\, dx \] [From the previous example:] \[ S(a) = \int_0^\infty e^{-ax}\cos bx\, dx = \dfrac{a}{a^2+b^2} \] Differentiate with respect to \(a\): \[ S'(a) = -\int_0^\infty xe^{-ax}\cos bx\, dx = \dfrac{(b^2-a^2)}{(a^2+b^2)^2} \]

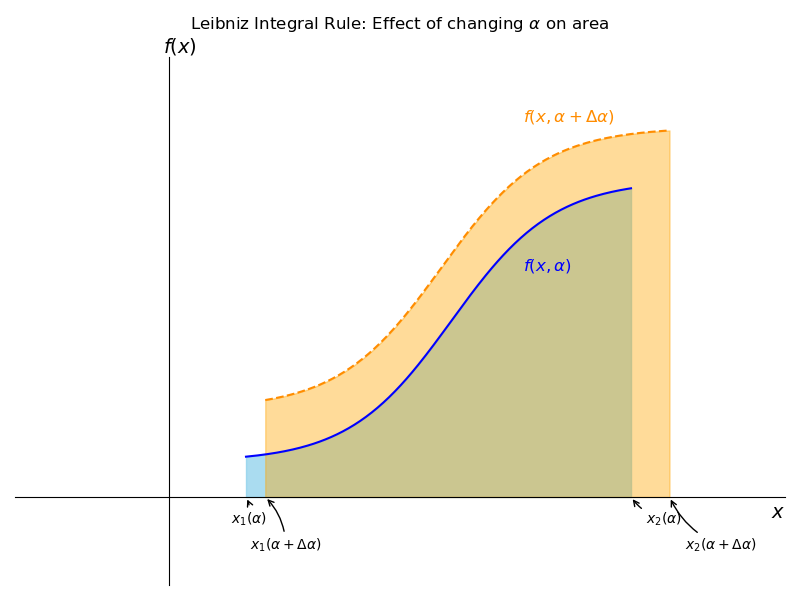

The general rule for differentiation with respect to a parameter is: \[ \dfrac{d}{d\alpha}\int_{x_1(\alpha)}^{x_2(\alpha)} f(x,\alpha)dx = \int_{x_1}^{x_2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial \alpha}f(x,\alpha)dx + \dfrac{d x_2(\alpha)}{d\alpha}f(x_2,\alpha) - \dfrac{d x_1(\alpha)}{d\alpha}f(x_1,\alpha) \]

\[ \Delta\int_{x_1}^{x_2} f(x,\alpha)dx = \int_{x_1}^{x_2}\Delta f(x,\alpha)dx + \Delta x_2(\alpha)f(x_2,\alpha) - \Delta x_1(\alpha)f(x_1,\alpha) \]

Explanation

The goal is to understand how the total area under a curve changes if:

- The shape of the curve itself changes.

- The start and end points of the integration move.

The parameter α (alpha) controls both the shape of the function and the positions of the integration limits, x₁ and x₂. The notes show what happens when you make a small change in this parameter, from α to α + Δα.

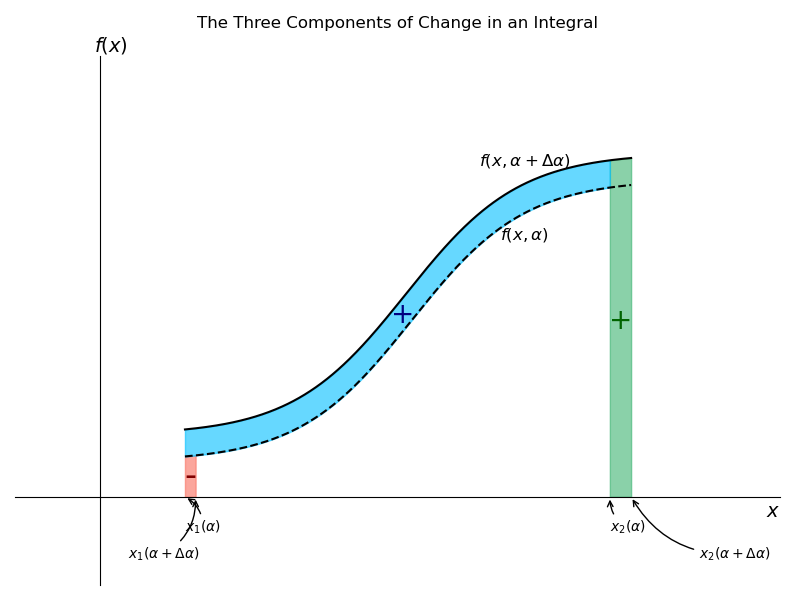

The diagram provides a visual breakdown of the total change in the area under the curve. Let’s look at the three distinct ways the area changes:

- The “Body” of the Area Changes (Shape Change):

- The lower curve is f(x, α).

- The upper curve is f(x, α + Δα).

- The change in the function’s height is Δf = f(x, α + Δα) - f(x, α).

- The area between these two curves is the main contribution to the change. This is represented by the first term in the final equation: ∫ Δf(x,α) dx.

- A Sliver of Area is ADDED on the Right (Upper Limit Moves):

- The upper limit of integration moves from x₂(α) to x₂(α + Δα).

- This adds a thin rectangular sliver of area on the far right.

- The width of this sliver is Δx₂.

- Its height is approximately f(x₂, α).

- This corresponds to the second term in the final equation: + Δx₂(α) f(x₂, α).

- A Sliver of Area is SUBTRACTED on the Left (Lower Limit Moves):

- The lower limit of integration moves from x₁(α) to x₁(α + Δα).

- This removes a thin rectangular sliver of area on the far left.

- The width of this sliver is Δx₁.

- Its height is approximately f(x₁, α).

- This corresponds to the last term in the final equation: - Δx₁(α) f(x₁, α).

The total change in the integral’s value is the sum of these three pieces.

Now dividing both sides by Δα, we have

$

\frac{\Delta\int_{x_1}^{x_2} f(x,\alpha)dx}{\Delta \alpha} = \int_{x_1}^{x_2}

\frac{\Delta f(x,\alpha)}{\Delta \alpha} dx + \frac{\Delta x_2(\alpha)}{\Delta \alpha}f(x_2,\alpha) - \frac{\Delta x_1(\alpha)}{\Delta \alpha}f(x_1,\alpha)

$

Taking the limit as $\Delta \alpha\to 0$, we obtain

$

\dfrac{d}{d\alpha}\int_{x_1(\alpha)}^{x_2(\alpha)} f(x,\alpha)dx = \int_{x_1}^{x_2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial \alpha}f(x,\alpha)dx + \dfrac{d x_2(\alpha)}{d\alpha}f(x_2,\alpha) - \dfrac{d x_1(\alpha)}{d\alpha}f(x_1,\alpha).

$

D. Multiplication by a Factor

Example: [Suppose we want to evaluate the following integral] \[ \int_0^\infty (\sin x/x)dx \] [To this end, let’s introduce a related integral that depends on a parameter \(\alpha\):] \[ \int_0^\infty e^{-\alpha x}\dfrac{\sin x}{x}dx = S(\alpha) \] \[ \begin{aligned} S'(\alpha) &= -\int_0^\infty e^{-ax}\sin x\ dx = -\frac{1}{1+\alpha^2} \\ S(\alpha) &= -\tan^{-1}\alpha+C \\ S(\infty) &= 0 = -\dfrac{\pi}{2}+C \\ S(\alpha) &= \dfrac{\pi}{2}-\tan^{-1}\alpha \\ S(0) &= \dfrac{\pi}{2} \end{aligned} \]

Explanation

Goal: Solve the famous Dirichlet integral, which does not have a simple antiderivative. > \[ \int_0^\infty \frac{\sin x}{x} dx \] Explanation: This is the problem we want to solve. We can’t find a simple function whose derivative is sin(x)/x, so standard integration methods won’t work easily.

Step 1: Introduce a Parameter > \[ \int_0^\infty e^{-\alpha x}\dfrac{\sin x}{x}dx = S(\alpha) \] Explanation: The trick begins here. We insert a “helper” term, e^(-αx), into the integral. This does two things: 1. It creates a new function that depends on the parameter α, which we call S(α). 2. It ensures the integral converges nicely for α > 0. Our goal is to find a formula for S(α) and then set α = 0, because e^(-0*x) = 1, which will give us the value of our original integral.

Step 2: Differentiate with Respect to the Parameter \[ S'(\alpha) = -\int_0^\infty e^{-\alpha x}\sin x dx = -\frac{1}{1+\alpha^2} \] Explanation: This is the key move. We differentiate S(α) with respect to α. The derivative can be moved inside the integral sign. * \(\displaystyle \frac{d}{d\alpha} \left(e^{-\alpha x} \frac{\sin x}{x}\right)=-x e^{-\alpha x} \frac{\sin x}{x}\). * The x in the numerator cancels the difficult 1/x term in the denominator. This leaves us with a much simpler integral: S'(α) = -∫ e^(-αx) sin(x) dx. This is a standard integral whose result is known to be 1 / (1 + α²). So, S'(α) = -1 / (1 + α²).

Step 3: Integrate Back to Find S(α) \[ S(\alpha) = -\tan^{-1}(\alpha)+C \] Explanation: To get from the derivative S'(α) back to the original function S(α), we integrate S'(α) with respect to α. The integral of -1 / (1 + α²) dα is -tan⁻¹(α). Because this is an indefinite integral, we must add an unknown constant of integration, C.

Step 4: Solve for the Constant C \[ S(\infty) = 0 = -\dfrac{\pi}{2}+C \] Explanation: To find C, we need to evaluate S(α) at a point where we know its value. A convenient choice is α → ∞. * Looking at our definition S(α) = ∫ e^(-αx) (sin x / x) dx, as α becomes very large, the e^(-αx) term becomes a “killer” term, forcing the entire integrand to zero for any x > 0. Therefore, the integral itself must be zero, so S(∞) = 0. * Using our formula from the previous step, S(∞) = -tan⁻¹(∞) + C. Since tan⁻¹(∞) = π/2, this gives us the equation 0 = -π/2 + C, which means C = π/2.

Step 5: Write the Final Formula and Get the Answer \[ S(\alpha) = \dfrac{\pi}{2}-\tan^{-1}\alpha \] Explanation: Now that we know C = π/2, we can write the complete formula for our function S(α).

\[ S(0) = \dfrac{\pi}{2} \] Explanation: This is the final step. We substitute α = 0 back into our formula to find the value of the original integral. * S(0) = π/2 - tan⁻¹(0) * Since tan⁻¹(0) = 0, the final answer is π/2.

Problem (a) Given \(\displaystyle \int_0^\infty e^{-a^2x^2}dx = \sqrt{\pi}/2a\) Prove: \[ \int_0^\infty e^{-a^2x^2}\cos bx\, dx = \dfrac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2a}e^{-b^2/4a^2} \]

(b) Given \(\displaystyle \int_0^\infty e^{-x^2}dx = \sqrt{\pi}/2\) Find: \[ \int_0^\infty x^4 e^{-x^2}dx \]

(c) \[\displaystyle \int_0^\infty dy(e^{-ay}-e^{-by})/y \]

(d) \[\displaystyle \int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-ax^2-b/x^2} dx \]

(e) \[\displaystyle \int_0^\infty dx \sin^2x/x^2 \]

E. Differentiation under Integral Sign

I.

Example: [Let’s consider the following difficult integral which depends on the parameter $a$] \[ \int_0^\infty e^{-ax}(1+x^2)^{-1}dx = S(a) \]

\[ \int_0^\infty x^2 e^{-ax}(1+x^2)^{-1}dx = S''(a) \] \[ S(a)+S''(a) = \int_0^\infty \left(\dfrac{1}{1+x^2}+\dfrac{x^2}{1+x^2}\right)e^{-ax}dx \] \[ \dfrac{d^2 S}{da^2}+S = \dfrac{1}{a} \] This differential equation may be solved for S(a).

Explanation

This example demonstrates a clever technique for solving a difficult integral by transforming it into a differential equation. The integral is first defined as a function, S(a), which depends on the parameter a. By taking the second derivative of S(a) with respect to a, a new integral for S’‘(a) is found. The key insight is to then add S(a) and S’‘(a) together. This allows the complicated parts inside the integral to combine and simplify algebraically, leaving a much simpler integral on the right-hand side that evaluates to just 1/a. As a result, the original problem is successfully converted into the more standard task of solving the second-order differential equation S’’ + S = 1/a to find the value of S(a).

II. Partial Differentiation

[Now let’s consider the following integral that is a function of two parameters, α and β.] \[ S(\alpha,\beta) = \int_0^\infty e^{-\alpha x}\sin (\beta x)\, dx \] \[ \begin{aligned} \dfrac{\partial^2 S}{\partial \alpha^2} &= \int_0^\infty x^2 e^{-\alpha x} \sin (\beta x)\, dx \\ \dfrac{\partial^2 S}{\partial \beta^2} &= -\int_0^\infty x^2 e^{-ax} \sin (\beta x)\, dx \\ \dfrac{\partial^2 S}{\partial \beta^2} &= -\dfrac{\partial^2 S}{\partial \alpha^2} \end{aligned} \]

Explanation

We differentiate under the integral sign twice. Differentiating with respect to α brings down (-x)² = x². Differentiating with respect to β brings down a factor of x twice from the sin(βx) and a minus sign from the second derivative of sine. We see that the two second partial derivatives are negatives of each other. This gives us a partial differential equation, which is the Laplace equation. Our integral is a solution to this equation.

The form of S may be partly determined by making the substitution \(y=\beta x\) \[ S(\alpha,\beta) = \beta^{-1} \int_0^\infty e^{-\frac{\alpha}{\beta}y}\sin y\, dy = \beta^{-1} F\left(\dfrac{\alpha}{\beta}\right) \]

Explanation

This is a dimensional analysis or “scaling” argument. By substituting y = βx, we can show that the integral’s dependence on α and β is not arbitrary; it must be a function of the ratio α/β, with a 1/β factor out front. We call this unknown function F. This step dramatically simplifies the problem by reducing two variables (α, β) to one (α/β).

\[ \begin{aligned} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial\beta}\left[\beta^{-1}F\left(\dfrac{\alpha}{\beta}\right)\right] &= -\frac{\alpha}{\beta^3}F'\left(\dfrac{\alpha}{\beta}\right)-F\beta^{-2} \\ \dfrac{\partial^2}{\partial\beta^2}\left[\beta^{-1}F\left(\dfrac{\alpha}{\beta}\right)\right] &= \dfrac{\alpha^2}{\beta^5}F''\left(\dfrac{\alpha}{\beta}\right)+\frac{3\alpha}{\beta^4}F' \\ &\qquad+F\frac{2}{\beta^3}+\frac{\alpha}{\beta^4} F'\\ \frac{\partial^2 S}{\partial \beta^2}&=\frac{2}{\beta^3}F+\frac{4\alpha}{\beta^4}F'+\frac{\alpha^2}{\beta^5}F''\\ \dfrac{\partial^2 S}{\partial\alpha^2} &= \dfrac{1}{\beta^3}F'' \end{aligned} \]

Explanation

Here, the second partial derivatives are re-calculated, but this time by applying the chain rule to the new form S = (1/β) F(α/β).

Multiply by \(\beta^3\) and let \(z=\dfrac{\alpha}{\beta}\) \[ 2F+4zF'+z^2F'' = -F'' \]

Explanation

We substitute the new expressions for the derivatives back into our Laplace equation ($S_{\alpha\alpha}+S_{\beta\beta}=0$) and let z = α/β. This turns the complex PDE into a simpler ordinary differential equation (ODE) for the function F(z).

\[ \dfrac{d}{dz}(z^2F') + 2\dfrac{d}{dz}(zF) = -F'' \] \[ z^2F'+2zF = -F'+C_1 \] \[ \dfrac{d}{dz}(z^2F) = -F'+C_1 \] \[ z^2F = -F+C_1 z + C_0 \] \[ F = (C_0+C_1 z)/(1+z^2) \]

Explanation

The ODE is now solved. We use a clever trick, noticing that some terms are the result of a product rule (d/dz (z²F) and d/dz (z²F')), which allows for direct integration. This process yields the general solution for F, which contains two unknown constants, C₀ and C₁

\[ S(\alpha,\beta) = \dfrac{1}{\beta}F = (C_0\beta+C_1\alpha)/(\alpha^2+\beta^2) \]

Explanation

We substitute back z = α/β and S = F/β to get the general form of our original integral. Now, all we need to do is find C₀ and C₁.

To evaluate \(C_0+C_1\) we observe: \[ S(\alpha,0)=0 = \dfrac{C_1\alpha}{\alpha^2}\quad \therefore C_1=0. \]

Explanation

We use a simple physical limit. If β=0, then sin(0*x) = 0, so the integral S(α,0) is clearly zero. Plugging β=0 into our general form gives C₁α / α². For this to be zero, C₁ must be zero.

For small \(\beta\), \(\sin\beta x \sim \beta x\). This is a good approximation since \(e^{-ax}\) kills the integrand for large x. \[ \int_0^\infty e^{-ax}\ \beta x\ dx = \dfrac{\beta}{\alpha^2} \] \[ \dfrac{C_0\beta}{\alpha^2+\beta^2} \approx \dfrac{C_0\beta}{\alpha^2} \qquad\therefore C_0 = 1 \]

Explanation

To find C₀, we use another approximation. For very small β, sin(βx) is approximately βx. We solve this much simpler approximate integral and find that it equals β/α².

We compare our general solution (with C₁=0) to the result from the approximation. For small β, (C₀β) / (α² + β²) ≈ (C₀β) / α². For this to match β/α², the constant C₀ must be 1.

[Therefore:] \[ S(\alpha,\beta) = \dfrac{\beta}{\alpha^2+\beta^2} \]