Pascal’s law is valid for liquids and gases. However, it fails to take into account an important circumstance—the existence of weight.

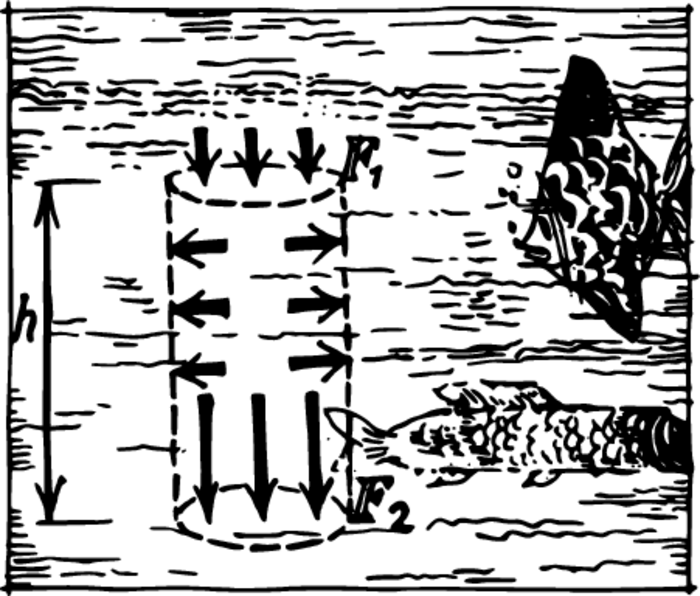

Under terrestrial conditions, this should not be forgotten. Even water has weight. It is therefore obvious that two area elements situated at different depths under water will experience different pressures. But what will this difference be equal to? Let us conceptually single out within a liquid a right cylinder with horizontal bases. The water inside it presses on the surrounding water. The resultant force of this pressure is equal to the weight \(mg\) of the liquid in the cylinder Figure 1. This resultant force is made up of the forces acting on the bases of the cylinder and on its lateral surface. But the forces acting on opposite sides of the lateral surface are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. Therefore, the sum of all the forces acting on the lateral surface is equal to zero. Hence, the weight \(mg\) will be equal to the difference in force, \(F_{2} - F_{1}\). If the height of the cylinder is \(h\), the area of its base is \(S\), and the density of the liquid is \(\rho\), we may write \(\rho g h S\) instead of \(mg\).

The difference in force is equal to this quantity. In order to obtain the difference in pressure, we must divide the weight by the area \(S\). The difference in pressure turns out equal to \(\rho gh\).

In accordance with Pascal’s law, the pressure on differently oriented area elements located at the same depth will be identical. Hence, at two points of a liquid situated one above the other at height \(h\) the difference in pressure will equal the weight of a column of the liquid whose cross-sectional area is equal to unity and whose height is \(h\): \[p_{2} - p_{1} = \rho gh\] A pressure exerted by water caused by its weight is called hydrostatic.

Under terrestrial conditions, air most often presses down on the free surface of a liquid. The pressure exerted by air is called atmospheric. The pressure at a depth is composed of atmospheric and hydrostatic pressures.

In order to compute the force due to water pressure, it is only necessary to know the size of the area element on which it is exerted and the height of the column of liquid above it. By virtue of Pascal’s law, nothing else plays any role.

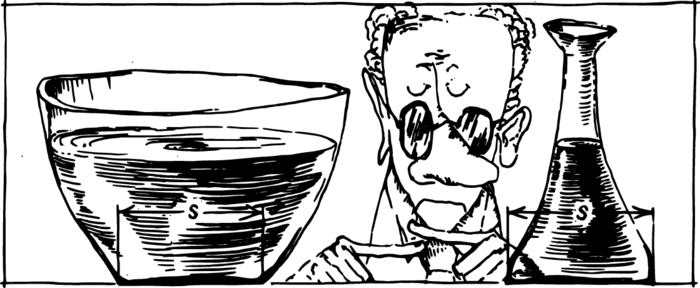

This may seem surprising. Is it possible for the forces acting on the identical bottoms of the two vessels depicted Figure 2 to be the same? Indeed, there is much more water in the vessel on the left. In spite of this, the forces acting on the bottoms are equal to \(\rho g h S\) in both cases. This is greater than the weight of the water in the vessel on the right and less than the weight of the water in the vessel on the left. The sloping walls of the vessel on the left support the weight of the “extra” water, but on the right, on the contrary, they add reaction forces to the weight of the water. This interesting phenomenon is sometimes called the hydrostatic paradox.

If two vessels of different form, but with water at the same level, are connected by means of a tube, water will not flow from one vessel to another. Such a flow could take place in case the pressures in the vessels were different. But this is not the case, and so the liquid in communicating vessels will always stand at one and the same level regardless of their form.

On the contrary, if the water levels in communicating vessels are different, water will begin moving and the levels will equalize.

Water pressure is much greater than air pressure. At a depth of 10 m, water pressure is twice atmospheric pressure, at a depth of 1 km, it is equal to 100 atm.

Oceans have depths greater than 10 km at certain places. The forces due to water pressure at such depths are exceptionally great. Pieces of wood which are lowered to a depth of 5 km are so compressed by this enormous pressure that, after such a “baptism”, they sink like bricks in a barrel of water.

This enormous pressure makes great difficulties for investigators of marine life. Deep-sea descents are carried out in steel globes—the so-called bathyspheres or bathyscaphes—-which have to withstand pressures greater than 1000 atm.

But submarines can dive to a depth of only 100–200 m.