The peculiarities of the world of rotating systems are not exhausted by the existence of radial gravitational forces. We shall become acquainted with still another interesting effect whose theory was presented in 1835 by the Frenchman Gaspard Gustave de Coriolis (1792–1843).

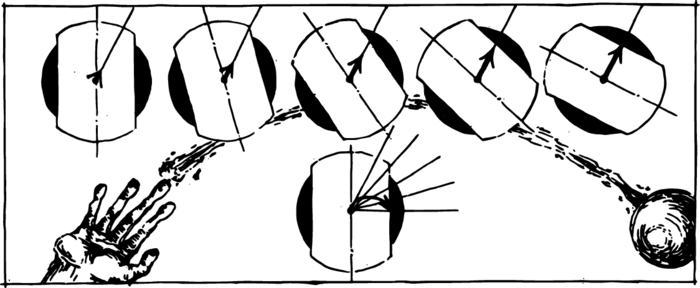

Let us pose the following question: What does rectilinear motion look like from the point of view of a rotating laboratory? A design of such a laboratory is depicted in Figure 1. The rectilinear trajectory of some body is shown by means of a ray passing through the centre. We are considering the case when the path of the body passes through the centre of rotation of our laboratory. The disc on which the laboratory is standing rotates uniformly; five positions of the laboratory with respect to the rectilinear trajectory are shown in the figure. This is how the relative positions of the laboratory and the trajectory of the body look after one, two, three, etc., seconds. The laboratory, as you see, is rotating counter-clockwise if looked upon from above.

Arrows corresponding to the segments through which the body passes during one, two, three, etc., seconds have been drawn on the line of its path. The body covers the same distance during each second, since we are dealing with uniform and rectilinear motion from the point of view of a fixed observer.

Imagine that the moving body is a freshly painted ball rolling along the disc. What kind of trace will remain on the disc? Our construction yields the answer to this question. The points which mark the ends of the arrows have been transferred from our five drawings to a single diagram. It remains to connect these points by a smooth curve. The result of our construction will not surprise us: rectilinear and uniform motion looks like curvilinear motion from the point of view of a rotating observer. The following rule attracts our attention: a moving body is deflected to the right of its path during the entire course of the motion. We now assume that the disc is rotating in the clockwise direction, and leave the repetition of our construction to the reader. It will show that, in this case, a moving body is deflected to the left of its path from the point of view of a rotating observer.

We know that a centrifugal force arises in rotating systems. However, its action cannot serve as the cause of the deformation of the path, for it is directed along the radius. Hence, besides the centrifugal force another additional force arises in rotating systems. It is called the Coriolis force.

Why is it that in the previous examples we did not come across the Coriolis force and managed superbly with only centrifugal? The reason is that until now we have not regarded motion from the point of view of a rotating observer, and a Coriolis force arises only in such a case. Only a centrifugal force is exerted on bodies which are, stationary in rotating systems. A table in a rotating laboratory is screwed on to the floor—only a centrifugal force is exerted on it. But on a ball which has fallen from the table and rolled along the floor of the rotating laboratory besides a centrifugal force a Coriolis force is also exerted.

On what quantities does the magnitude of a Coriolis force depend? It can be calculated, but the computations are too complicated to be given here. We shall therefore present only the result of these computations.

Unlike a centrifugal force whose magnitude depends on the distance from the axis of rotation, a Coriolis force is independent of the position of a body. It is determined by the velocity vector (i.e. not only by its magnitude, but also by its direction with respect to the axis of rotation). If the body moves along the axis of rotation, the Coriolis force is equal to zero. The greater the angle between the velocity vector and the axis of rotation, the greater will be the Coriolis force; this force assumes its maximum value when the motion of the body is at right angles to the axis. As we know, it is always possible to decompose a velocity vector into any pair of its components and consider separately the two resulting motions in which the body is simultaneously involved.

If the velocity of a body is decomposed into components \(v_{\parallel}\) and \(v_{\perp}\)—parallel and perpendicular to the axis of rotation—then the first motion will not be subject to the action of a Coriolis force. The magnitude of the Coriolis force \(F_{C}\) is determined by the component \(v_{\perp}\) of the velocity. Computations lead to the formula \[F_{C}= 4 \pi n v_{\perp} m\] Here \(m\) is the mass of the body, and \(n\) is the number of revolutions made by the rotating system in a unit of time. As can be seen from the formula, the faster the system rotates and the faster the body moves, the greater will be the Coriolis force.

Calculations also established the direction of a Coriolis force. This force is always perpendicular to the axis of rotation and the direction of the motion. Moreover, as has already been said above, the force is directed to the right of its path in a system rotating counterclockwise.

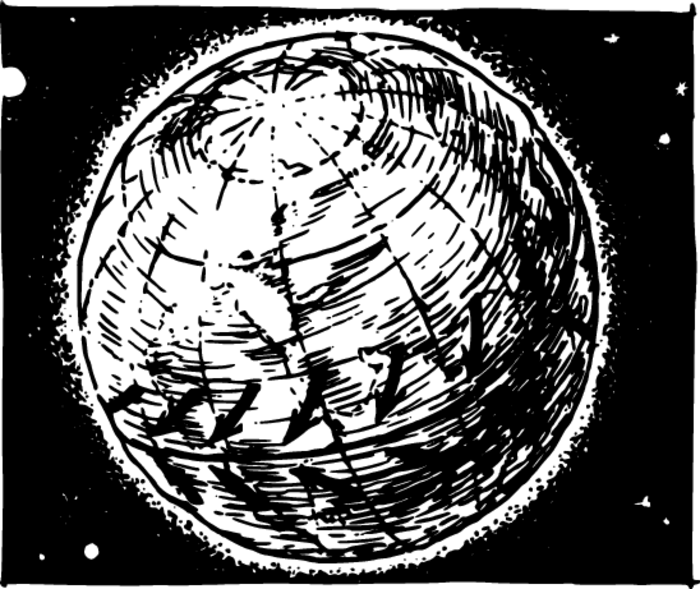

Many interesting phenomena occurring on the Earth are explained by the action of Coriolis forces. The Earth is a sphere, and not a disc. This makes the effect of Coriolis forces more complicated. These forces will not only influence motion along the Earth’s surface but also the falling of bodies to the Earth.

Does a body fall exactly along a vertical? Not quite. Only at a pole does a body fall exactly along a vertical. Here the direction of the motion and the Earth’s axis of rotation coincide, so there is no Coriolis force. The situation is different at the equator; here the direction of the motion forms right angles with the Earth’s axis. If looked upon from the North Pole, the Earth’s rotation will appear to be counterclockwise. Hence, a freely falling body should be deflected to the right of its path, i.e. to the East. The magnitude of this eastward deflection, the greatest at the equator, decreases to zero as the poles are approached.

Let us compute the magnitude of the deflection at the equator. Since a freely falling body moves with a uniform acceleration, the Coriolis force increases as the Earth is approached. We shall therefore restrict ourselves to an approximate computation. If the body falls from a height, say, of 80 m, its fall will last about 4 s according to the formula \(t = \sqrt{2h/g}\). The average speed for the fall will be equal to 20 m/s.

This is the speed that we shall substitute in our formula for the Coriolis acceleration, \(4 \pi n v\) Let us convert the value \(n = 1\) revolution in 24 hours to the number of revolutions per second; \(24 \times 3600\) seconds are contained in 24 hours, so \(n\) is equal to 1/86,400 rps: consequently, the acceleration created by the Coriolis force is equal to \(\pi/1080~\mathrm{m/s^2}\). The distance covered during 4 s with such an acceleration is equal to \((1/2) (\pi/1080) \times 4^{2} = 2.3~\mathrm{cm}\). This is precisely the magnitude of the eastward deflection in our example. An exact computation, taking into account the non-uniformity of the fall, yields a close but somewhat different number.

While the deflection of a freely falling body is maximum at the equator and equal to zero at the poles, we shall see the opposite picture in the case of the deflection of a body moving in a horizontal plane under the action of a Coriolis force.

A horizontal site on the North or South Pole does not differ at all from the rotating disc with which we began our study of Coriolis forces. A body moving along such a site will be deflected to the right of its path by the Coriolis force at the North Pole, and to the left at the South Pole. Using the same formula for the Coriolis acceleration, the reader can calculate without difficulty that a bullet fired from a rifle with an initial speed of 500 m/s will be deflected from the target by 3.5 cm in a horizontal plane during one second (i.e. while it travels 500 m).

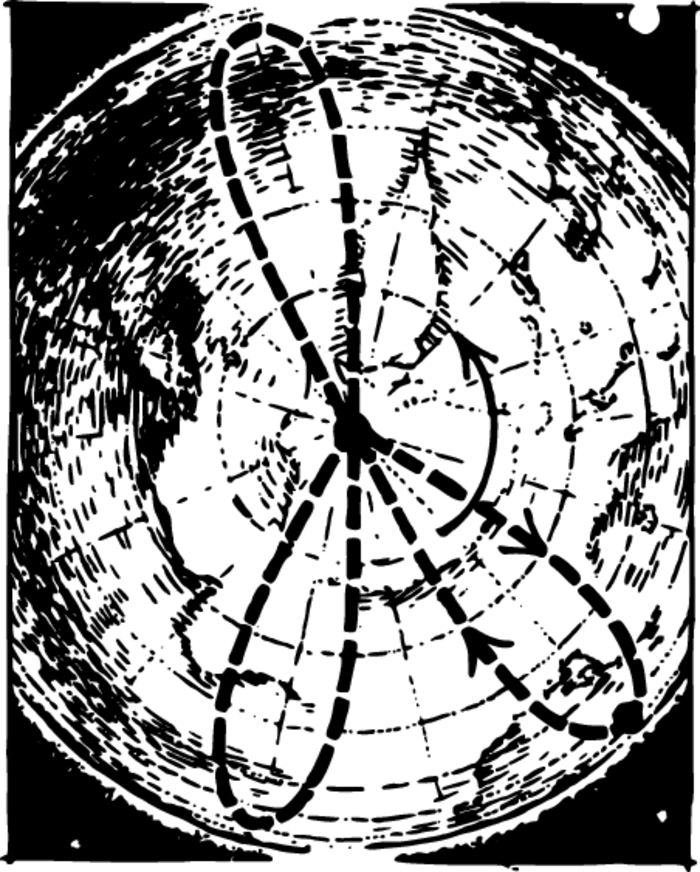

But why should the deflection in a horizontal plane at the equator be equal to zero? Without rigorous proofs, it is clear that this should be the case. At the North Pole a body is deflected to the right of its path, and at the South Pole to the left, hence, half-way between the poles, i.e. at the equator, the deflection will be equal to zero. Let us recall the experiment with the Foucault pendulum. A pendulum oscillating at a pole preserves the plane of its oscillations. The Earth in its rotation moves away from under the pendulum. This is how the stellar observer explains the Foucault experiment. But the observer rotating together with the Earth explains this experiment by means of a Coriolis force. As a matter of fact, a Coriolis force is directed perpendicularly to the Earth’s axis and perpendicularly to the direction of the motion of the pendulum; in other words, the force is perpendicular to the plane of the oscillation of the pendulum and will continually turn this plane. It can be arranged so that the end of the pendulum traces the trajectory of the motion. This trajectory is represented by the “rosette” shown in Figure 2. It can be seen from this figure that the “Earth” completes one quarter of a rotation during one and a half periods of the oscillation of the pendulum. The Foucault pendulum turns much more slowly. At a pole, the plane of oscillation of the pendulum will turn through one-fourth of a degree during one minute. At the North Pole the plane will be turned to the right of the path of the pendulum, and at the South Pole to the left.

The Coriolis effect will be somewhat less at Central European latitudes than at the equator. A bullet in the example we have just given will be deflected not by 3.5 cm but by 2.5 cm. The Foucault pendulum will be turned by about one-sixth of a degree during one minute.

Must a gunner take the Coriolis force into account? Big Bertha used by the Germans to shell Paris during World War I was situated 110 km from the target. The Coriolis deflection is as much as 1600 m in such a case. This is no longer a small quantity. If a flying projectile is sent very far without taking the Coriolis force into account, it will be deflected significantly from its course. This effect is large not because the force is great (for a ten ton projectile having a speed of 1000 km/h, the Coriolis force will be about 25 kgf but because it is exerted continually for a long period of time.

Of course, the influence of wind on a rocket projectile may be no less significant. Flight corrections made by a pilot depend on the action of the wind, the Coriolis effect and imperfections in the airplane or flying bomb.

What specialists besides aviators and gunners should be aware of the Coriolis effect? Strange as it may seem, among such specialists are railroaders. Under the action of the Coriolis force, one of the rails of a railroad wears out on the inside noticeably more than the other. We know just which one: in the Northern Hemisphere it will be the right rail (relative to the motion of a train), and in the Southern Hemisphere the left one. Only the railroaders in equatorial countries are saved from trouble in connection with this.

The washing away of right banks in the Northern Hemisphere is explained in exactly the same way as the wearing out of rails. The deviation of a river bed is to a large extent related to the action of the Coriolis force. It turns out that rivers in the Northern Hemisphere pass obstacles on the right.

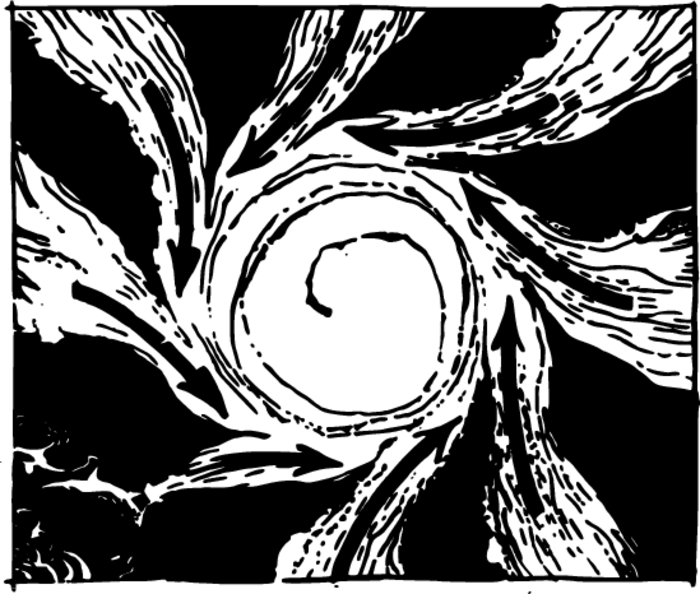

It is known that streams of air flow into a low-pressure area. But why is such a wind called a cyclone? After all, the root of this word suggests a circular (cyclic) motion.

This is precisely the case—a circular motion of air masses arises in a low-pressure area (Figure 3). The cause lies in the action of the Coriolis force. In the Northern Hemisphere all air streams directed towards the low-pressure area are deflected to the right of their motion. Take a look at Figure 4—you see that this leads to a westward deflection of the winds blowing in both hemispheres from the tropics to the equator (trade-winds).

Why does such a small force play such a big role in the motion of air masses? This is explained by the insignificance of the frictional forces. Air is extremely mobile, and a small but constantly acting force can lead to important consequences.