Bertold, a hero of Pushkin’s Scenes from the Days of Knighthood, dreamed of bringing about perpetuum mobile.

“What is perpetuum mobile?” asks his interlocutor. “It is perpetual motion,” answers Bertold. “If I find perpetual motion, I see no bounds to human creativity. To make gold is a tempting problem, a discovery can be curious and profitable, but to find a solution to the problem of perpetuum mobile …”

Perpetuum mobile, or a perpetual motion machine, is a machine working not only contrary to the law of loss of mechanical energy, but also in violation of the law of conservation of mechanical energy, which, as we now know, holds only under ideal unattainable conditions—in the absence of friction. A perpetual motion machine must, as soon as it is constructed, begin working “by itself”, for example, turning a wheel or lifting up a load. This work should take place perpetually and continually, and the machine should require neither fuel nor human hands nor the energy of falling water—in short, nothing got from without.

The earliest reliable document known so far dealing with the “realization” of a perpetual motion machine goes back to the 13th century. It is a curious fact that after six centuries, in 1910, exactly the same “project” was presented for “consideration” in one of Moscow’s scientific institutions.

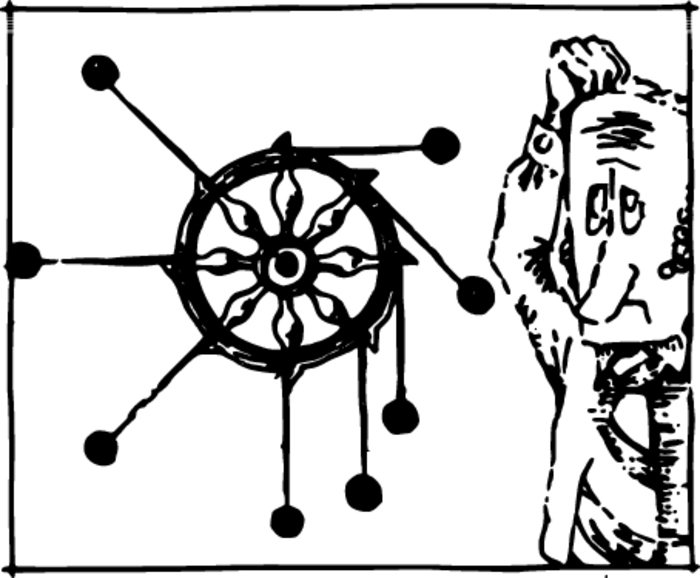

The project for this perpetual motion machine is depicted in Figure 1. As the wheel rotates, the loads are thrown back and, according to the inventor, support the motion, since these loads, acting at a greater distance from the axis, press down much harder than the others. Having constructed this by no means complicated “machine”, the inventor convinces himself that after turning once or twice by inertia, the wheel comes to a halt. But this does not make him lose heart. An error has been committed: the levers should have been made longer, the protuberances must be changed in form. And the fruitless labour to which many self-made inventors have devoted their lives continues, but of course with the same success.

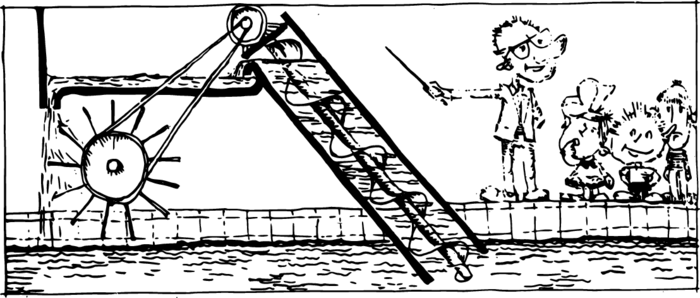

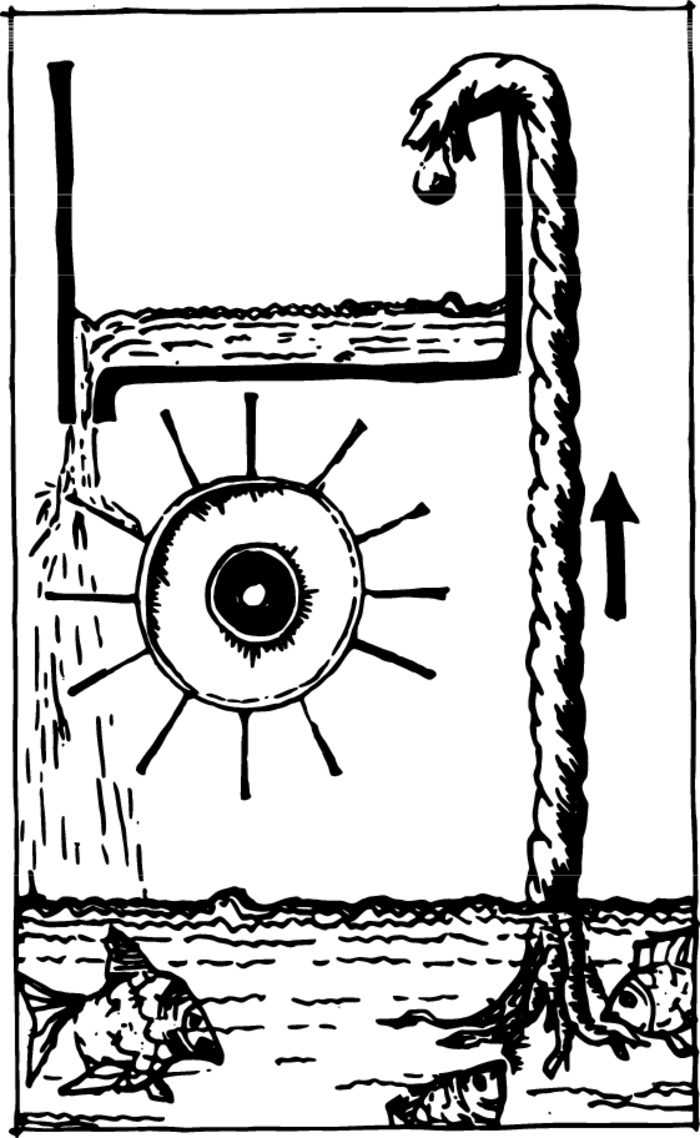

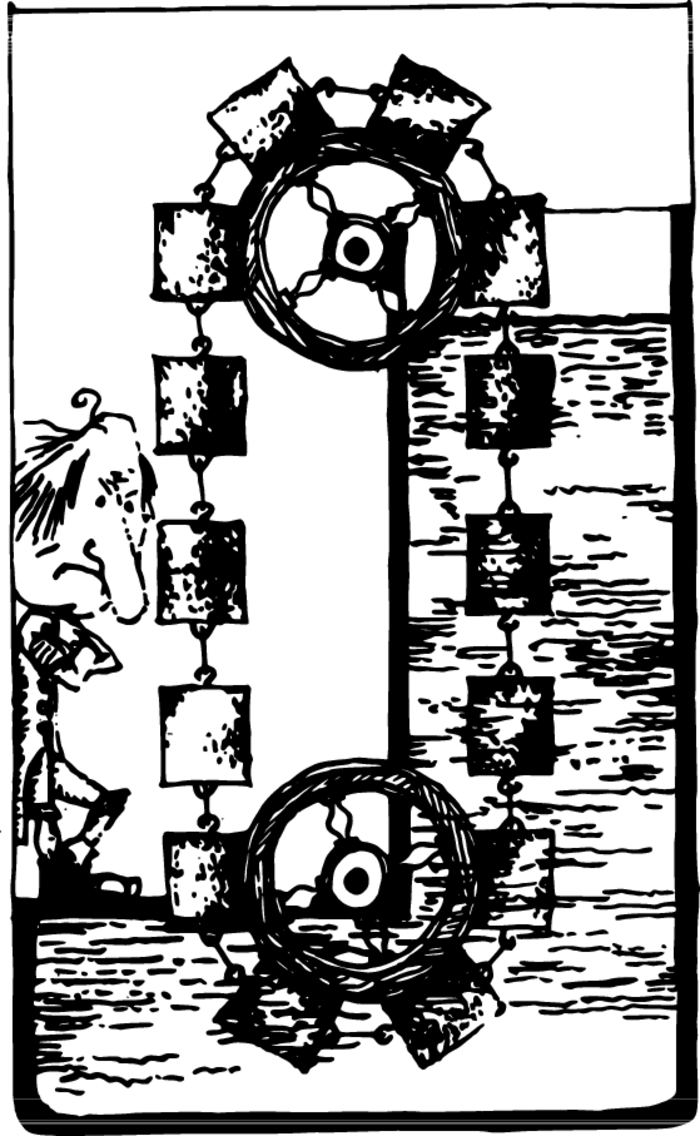

On the whole, there have not been many variants of proposed perpetual motion machines: various self-moving wheels not differing in principle from the one described; hydraulic machines, for example, the machine shown in Figure 2, which was invented in 1634; machines using siphons or capillary tubes (Figure 3), the loss of weight in water (Figure 4) or the attraction of iron bodies to magnets. It is by no means always possible to guess at the expense of what, according to the inventor, the perpetual motion should have occurred.

Even before the law of conservation of energy was established, we find the assertion of the impossibility of perpetuum mobile in an official declaration of the French Academy, made in 1775, when it decided not to accept any more projects for perpetual motion machines to be examined and tested.

Many 17th and 18th century physicists had already assumed the axiom of the impossibility of perpetuum mobile as a basis of their proofs, in spite of the fact that the concept of energy and the law of conservation of energy entered science much later.

At the present time it is clear that inventors who try to create a perpetual motion machine not only come into contradiction with experiment, but also commit an error in elementary logic, for the impossibility of perpetuum mobile is a direct consequence of the laws of mechanics, which is what they proceed from in justifying their “inventions”.

In spite of their complete fruitlessness, searches for perpetual motion machines probably played, nevertheless, some sort of useful role, since they led in the final analysis to the discovery of the law of conservation of energy.